The Rothschild family’s “Five Arrows” insignia, representing the “strength in unity” of the five dynasties established by the sons of the founder, in London, in 1962. The London and Paris branches eventually merged to form Rothschild & Co. Source: Evening Standard/Hulton Archive

The dynasty’s Swiss and French branches are engaged in a global fight to leverage the Rothschild name to win a bigger piece of the lucrative wealth management pie. The odds are rising that the only way forward for both would be a merger.

One of Ariane de Rothschild’s bankers returned from the Middle East a few months ago with some troubling news for her Swiss private bank, Edmond de Rothschild Group.

A prized, multi-millionaire client told him another representative of the firm had come calling — only, the business card the customer showed him had the logo of Rothschild & Co, a rival Paris-based entity run by Ariane’s estranged cousins-in-law.

It wasn’t the first time a client had confused the Swiss firm with its French competitor, but it was becoming an increasingly common problem. The two firms carrying the storied Rothschild name are the only remaining banks with links to the renowned family of financiers that emerged from Frankfurt’s Jewish ghetto more than two centuries ago to become one of the world’s richest and most powerful dynasties in the 19th century.

After decades of operating in relatively different business areas, they’re now engaged in a turf battle for a bigger piece of the highly lucrative $250 trillion global wealth management industry. And the odds are rising that within a generation a marriage of the two Rothschild entities will become imperative to keep the empire strong, people familiar with the matter say.

“They are now targeting similar clients,” said Christoph Künzle, a lecturer on wealth management at Zurich University of Applied Sciences. “It’s very competitive and their centuries-old name is a big asset that they are both trying to leverage.”

A settlement more than five years ago of a bitter legal dispute — initiated by Ariane — over the use of the Rothschild name should have put the conflict to bed. But it has done little to prevent the brand from becoming a key weapon in the cut-throat competition for rich customers across Europe, the Middle East and Asia.

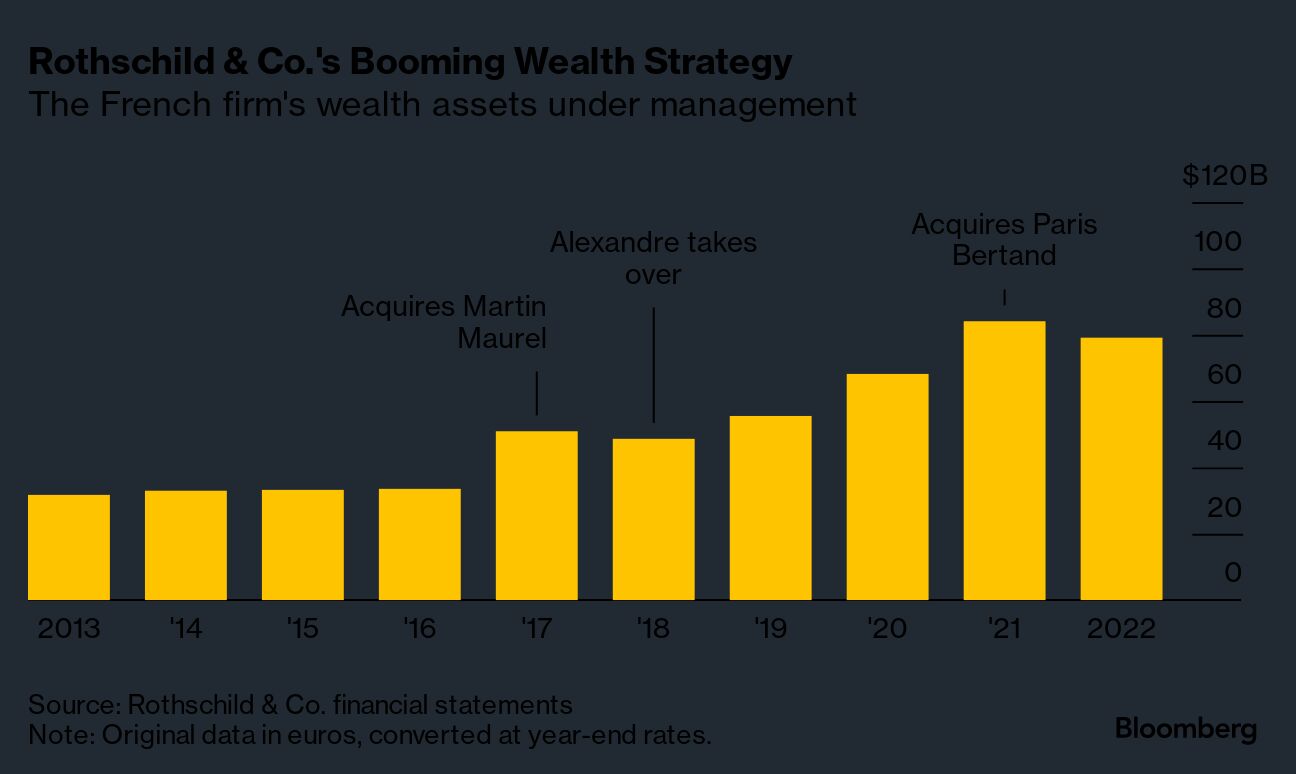

With over $100 billion in assets under management, Paris-based Rothschild & Co. is the smaller of the two, but it’s rapidly gaining ground by opening offices in the same playgrounds of the wealthy as its Swiss rival. For the first time in the firm’s history, pre-tax profit from wealth and asset management surpassed that from its advisory business in the first half of 2023. Already at the end of 2022, the Paris firm was closing in on its Swiss rival in terms of wealth assets.

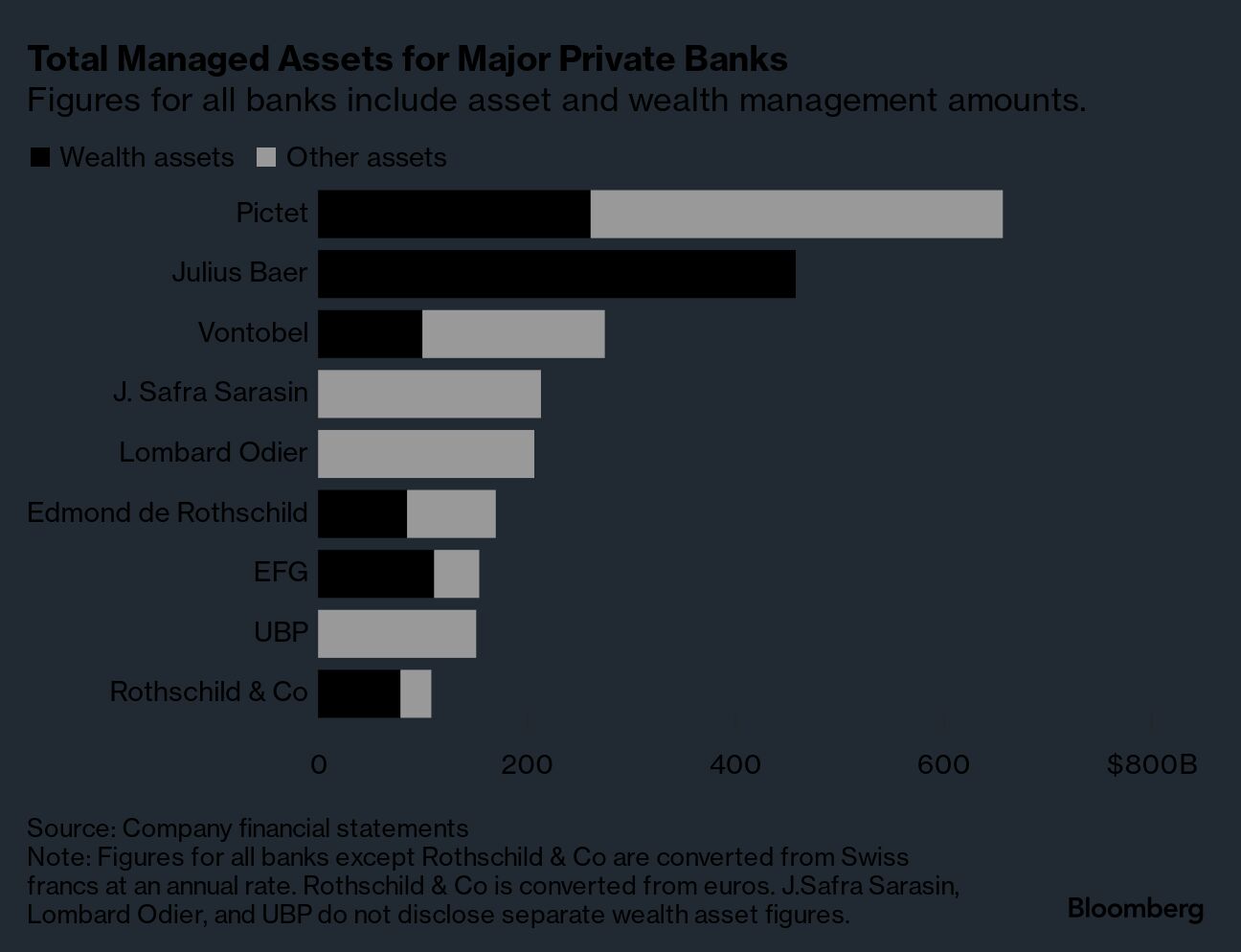

Joining forces would give heft to the Rothschild banks, which are minnows set against global industry behemoths like Morgan Stanley and UBS Group AG or even Swiss private banks Julius Baer Group Ltd. and Banque Pictet & Cie SA.

“There is a need for consolidation, notably for small wealth managers due to the increase in costs and regulation,” Nicolas Payen, an analyst at Kepler Cheuvreux, said of the sector. “A rule for the industry now is that they need size.”

A joint Rothschild entity would still be small relative to the giants of investment banking and wealth management, but it would employ about 7,000 people in offices from Amsterdam and Los Angeles to Tokyo, with a strong presence in continental Europe. At end-2022, the combined firm would have had about $280 billion in assets under management, leapfrogging Lombard Odier and Bank J. Safra Sarasin AG, and inching ahead of Vontobel Holding AG.

The idea of a rapprochement has been proposed by the French branch in the past, but turned down by the Swiss side. Rothschild & Co. Executive Chairman Alexandre de Rothschild and his father David aren’t coy about wanting a merger, colleagues at the firm said. The bank used acquisitions to jump start its wealth business and poaches entire teams from other firms. They’ve continued to make overtures to Ariane, but to no avail.

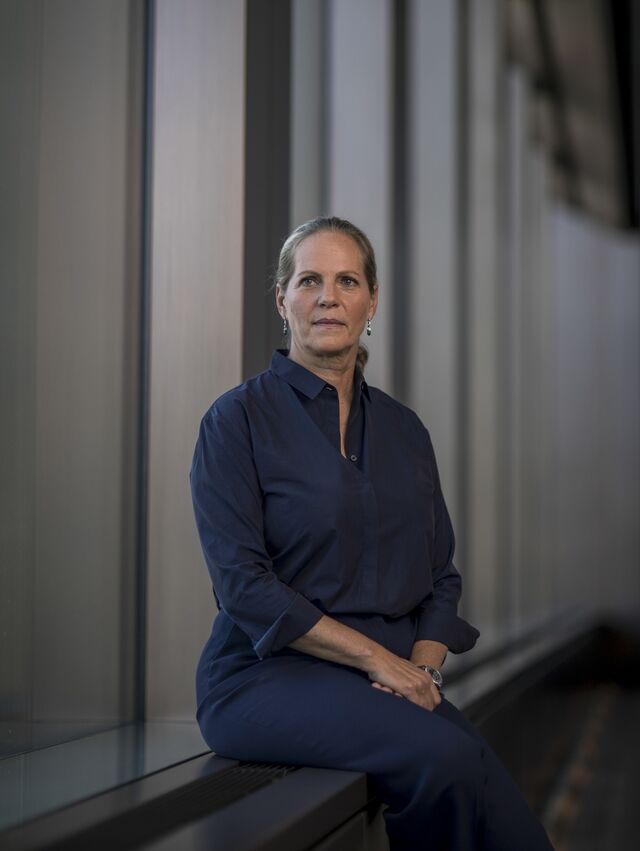

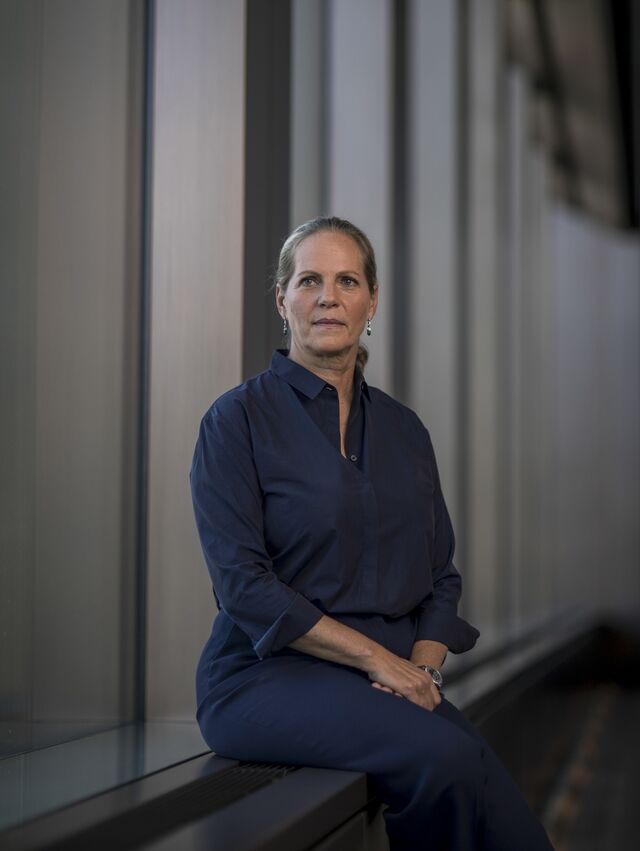

Even some of Ariane’s high-ranking private bankers see the rationale, but the 58-year-old has repeatedly rejected any suggestion of a combination, most recently saying in an interview with Le Matin in September that her four daughters will “ensure succession.” Still, it remains to be seen how wedded the daughters are to the bank.

Some bankers at the Swiss firm also say business has stagnated in recent years, partly because of what they see as a lack of vision. The bank counters that view, saying it has a clear strategy in place and will publish strong results for 2023 in March.

“On the one side there is an economic rationale, on the other there is personal pride,” said Philippe Pelé-Clamour, adjunct professor at business school HEC Paris who specializes in family firms. “This period of egos and disputes is relatively short when set against two centuries of history… A coming together could happen in the next generation.”

Total Managed Assets for Major Private Banks

Figures for all banks include asset and wealth management amounts.

Note: Figures for all banks except Rothschild & Co are converted from Swiss francs at an annual rate. Rothschild & Co is converted from euros. J.Safra Sarasin, Lombard Odier, and UBP do not disclose separate wealth asset figures. Source: Company financial statements

Neither Ariane, who carries the title baroness, nor Alexandre agreed to be interviewed for this article, which is based on conversations with more than a dozen current and former executives at both banks and outside observers who spoke on condition of anonymity. Representatives for the two banks said they don’t comment on speculation related to the firms or the Rothschild families.

For all their differences, the two sides share a common history that goes back to Mayer Amschel Rothschild, who founded a financial empire in Frankfurt and sent four of his five sons in the early 1800s to establish bases in London, Paris, Naples and Vienna, with the oldest staying home. Over the next 200 years, the extended family spawned one of Europe’s most famous banking dynasties, bankrolling wars and empires and helping shape the region’s economic and political history.

The London and Paris sides were the clan’s success stories. The Paris branch financed post-Revolution France and funded industries after World War II, employing generations of bankers, including two presidents, Georges Pompidou and Emmanuel Macron. In the UK, N.M. Rothschild & Sons famously helped fund the Duke of Wellington’s victory over Napoleon in the battle of Waterloo. In 2003, the London and Paris branches began merging into what is now Rothschild & Co.

In contrast, the Swiss firm is relatively new. Fifth-generation founder Edmond, born into the French branch of the family, started his bank in 1953. The firm helped very rich people discreetly move their savings in an era when private banking in Switzerland was less regulated and opaque, effectively sheltering them from high taxes in post-war Europe.

The two Rothschild entities operated in different segments, with the Swiss branch specializing in private banking at home and in places like Luxembourg and Monaco, and the Paris firm combining with the UK offshoot to rise to the top echelons of global corporate dealmakers. They even had cross shareholdings, and in the 1980s Edmond de Rothschild helped his Paris cousins get back on their feet after their bank was nationalized by Socialist French President François Mitterrand.

When Edmond died in 1997, his only son Benjamin, then 34, became chairman. More passionate about the bank’s Gitana sailing team and pursuits like hunting and skiing, Benjamin elevated his wife, Ariane, to deputy chairman in 2009. In 2021, Benjamin died of a heart attack at the age of 57.

As with many rich dynasties, the Rothschilds had their share of family intrigues and animosities. Relations between the Swiss and French cousins were awkward. Edmond’s branching off as banker to the rich — which at one point made him the clan’s wealthiest member — was a cause for jealousy, a person familiar with the families said. Also, Benjamin’s apparent lack of interest in the business was a sore point for his French cousins, the person said. Even within the same family, relationships could be prickly — Benjamin’s mother Nadine moved part of her fortune to Swiss rival Pictet some years ago to protest the way her late husband’s bank was being run by her son and daughter-in-law.

For years, the family name was a bone of contention for the two sides. Matters came to a head in 2015 when Ariane, in her first stint as CEO, took the Paris firm — which was using the name as a stand-alone in presentations — to court over the issue. The dispute was settled in 2018 in an accord that unwound cross-shareholdings and set parameters for how the name would be used and protected.

Now, each bank is at its own critical juncture, searching for growth and hell-bent on getting it by leveraging the Rothschild name — a brand exuding affluence after the family’s financial acumen allowed it over the years to accumulate the trappings of great wealth like mansions, vineyards, artwork, yachts and race horses.

“The Rothschilds have an asset that other financial institutions don’t, which is their historical reputation and the family’s wider portfolio of business interests,” said Sebastian Dovey, a former wealth management industry consultant who sits on the boards of a number of the sector’s firms.

At Rothschild & Co.’s elegant Art Nouveau building in central Paris, seventh-generation scion Alexandre, 43, is aggressively accelerating his father David’s strategic move into wealth. The firm had total assets under management of €102 billion ($110 billion) in mid-2023 — twice the 2015 level. In 2022, it said it plans to double managed assets in seven to 12 years.

Alexandre joined the bank in 2008, climbing the ranks before taking the top job from his father in 2018. Last year, he took Rothschild & Co. private, withdrawing it from the Paris stock market just months after corporate deal-making — its biggest business — started to dry up amid an industry-wide slump.

His march into the wealth business is gathering pace. In a highly symbolic move, in 2022 Rothschild & Co. opened a wealth-management office near Tel Aviv, landing it smack in the historic stomping grounds of Edmond de Rothschild. The Swiss bank, with strong philanthropic ties to Israel, has wooed rich clients there for decades from its offices on Rothschild Boulevard.

Rothschild & Co.’s Booming Wealth Strategy

The French firm’s wealth assets under management

Note: Original data in euros, converted at year-end rates. Source: Rothschild & Co. financial statements

Alexandre also added wealth specialists in Guernsey, Italy, Luxembourg and the UK, most of which are places where Edmond de Rothschild has strong footholds. In 2021, the French firm made an acquisition in Switzerland, Ariane’s backyard. In cities like Bordeaux and Toulouse, the two banks have offices just a short walk from each other. Both are focusing on expanding in the Middle East.

In January, the Paris bank added another wealth banker in its Madrid office, which is on the same street as the Swiss firm. This spring it will open a new unit in Hamburg, its third in Europe’s biggest economy after Frankfurt and Dusseldorf.

“Among consumers there is definitely confusion between the two,” said Declan Ahern, a strategy and valuations director at Brand Finance. “As their businesses grow, they’ll move into each other’s territories and create greater confusion. There could be more legal loggerheads down the line.”

Rothschild & Co.’s aggressive push into Edmond de Rothschild’s turf has come as Ariane grapples with issues of succession following her husband’s sudden death. The bank has also experienced upheaval in the corporate suite with three CEOs in the past five years, and stagnating business. Assets under management were down to 158 billion Swiss francs ($179 billion) at the end of 2022 from 178 billion francs the year before.

And although Ariane had set a goal of managing 350 billion francs by 2026, with no acquisitions in sight, that target seems ambitious. The firm told Bloomberg News it is continuing to look at acquisitions within its “strict M&A framework.” Results for last year will show double-digit growth in operating income and net new assets of 11 billion Swiss francs, it said.

Ariane, who stepped down as CEO in 2019, retook the reins at the bank’s headquarters in central Geneva last year and has increasingly become the face of the bank. She brought together what were essentially separate operations headed by warring egos in Paris, Geneva, Luxembourg and Monaco.

She also folded assets like wines, cheeses, hospitality and perfume into the bigger group to make them more accountable. But that prompted some senior staff to say she cares more about this ‘Heritage’ division than banking. At a town hall meeting in 2022 to discuss annual performance, Ariane left many bankers perplexed by speaking mainly about the perfume brand Caron she’d just relaunched.

Her judgment was also questioned when court documents in New York revealed in January that she had held more than a dozen meetings with convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein, discussing business deals and also staffing and furnishings. Ariane had no knowledge of Epstein’s personal conduct, and was shocked and horrified when she learned of it, the bank said.

Arian’s ascension to the helm of the bank, she says, was seen by some as controversial from the start due to her relative inexperience. As she shook things up, she said in a 2020 Bloomberg TV interview that some bankers initially regarded her as “a joke.”

The daughter of a German pharmaceutical executive and a French mother, she had an international upbringing, earned an MBA from Pace University in New York and worked on the currencies desks at Societe Generale SA and American International Group Inc. before meeting Benjamin and marrying him in the 1990s.

She has now staked Edmond de Rothschild’s near-term future on expanding in the Middle East, where banks and money managers the globe over are vying for the billions in oil wealth that might be invested outside the region. She’s also looking to reenter the now-crowded Asian market — after pulling back in 2016 from a costly, more than two-decade-long presence there.

While some private bankers applaud her willingness to pursue new territories, others say she hasn’t smoothed out businesses in Europe and lacks a long-term vision.

Still, her prominent role at the bank is key to attracting new, younger clients with more diverse sources of riches, as a global generational wealth transfer gathers steam, says Pedro Araujo, a senior researcher at the University of Fribourg who has studied Switzerland’s elite families.

“Ariane is very important for their brand image, to show that they’re in step with changes in society,” he said. “Private Swiss banks haven’t stood for diversity in the past.”

Ariane often points to Edmond de Rothschild as perhaps the world’s only bank that’s 100% owned by women: Benjamin’s heirs, his mother and a half sister. While she has insisted on the firm’s independence, Ariane has also said she wants her daughters to do whatever they want to do. So the big question is: Will the Swiss family come around at some point to join forces with its Paris cousins?

The one area where the families work together, more or less harmoniously, is in the French wine-growing regions of Bordeaux and Champagne. One of the country’s most prestigious vineyards, Chateau Lafite Rothschild, has been in the family since 1868.

Producing bottles that have sold for as much as $230,000 each, the winery counted Benjamin and founders of Rothschild & Co., David and Eric, among shareholders. According to a banker, Ariane had once objected to the rival bank’s use of the elegant property for promotional events, but tensions on the matter have since eased. In 2005, the families chose to create a brand together in Champagne.

The vineyards of Chateau Lafite Rothschild in the Bordeaux region. Photographer: Sebastien Ortole/REA/Redux

Still, those collaborations say little about their willingness to work together in their main banking businesses. Tellingly, when Alexandre took Rothschild & Co. private last year, he got the financial backing of four wealthy European dynasties, but, unlike in the 1980s, no capital came from Edmond de Rothschild.

So at least for now, each side will ride the family name in its fight for the world’s wealthy, and business cards will continue to spark confusion. As the late Benjamin de Rothschild rather presciently said in a 2010 interview: “It’s not clear how much our businesses are worth without the name.”