More than sixty-five million people ages 65 and older and younger people with long-term disabilities receive their health insurance coverage through the federal Medicare program. While overall satisfaction with the program is high, the financial burden of health care spending can prove challenging for Medicare beneficiaries. According to a recent KFF survey, more than one-third (36%) of Medicare beneficiaries said they have delayed or gone without a visit to the doctor’s office, vision services, hearing services, prescription drugs or dental care within the last year because of the cost. Medicare households also spend a larger share of their total budgets on health care than non-Medicare households, and are more likely to need expensive long-term services and supports over an extended period of time which are not covered by Medicare.

This brief examines the income, assets, and home equity of Medicare beneficiaries, overall and by age, race and ethnicity, and gender, using data derived from the Dynamic Simulation of Income Model (DYNASIM) for 2023. Due to data limitations, estimates for beneficiaries in some racial and ethnic groups, including Asian, American Indian and Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander beneficiaries, as well as beneficiaries who identify as two or more races, are unavailable (see Methods for additional details on the model).

This analysis highlights that most Medicare beneficiaries live on relatively low incomes and have modest financial resources to draw upon in retirement if they need to cover costly medical care or long-term services and supports, with notable disparities by age, race and ethnicity, and gender. For example:

- One in four Medicare beneficiaries lived on incomes below $21,000 per person in 2023, while half lived on incomes below $36,000 per person. Median income declined with age among older adults, was lower for women than men, and lower for Black and Hispanic than White beneficiaries.

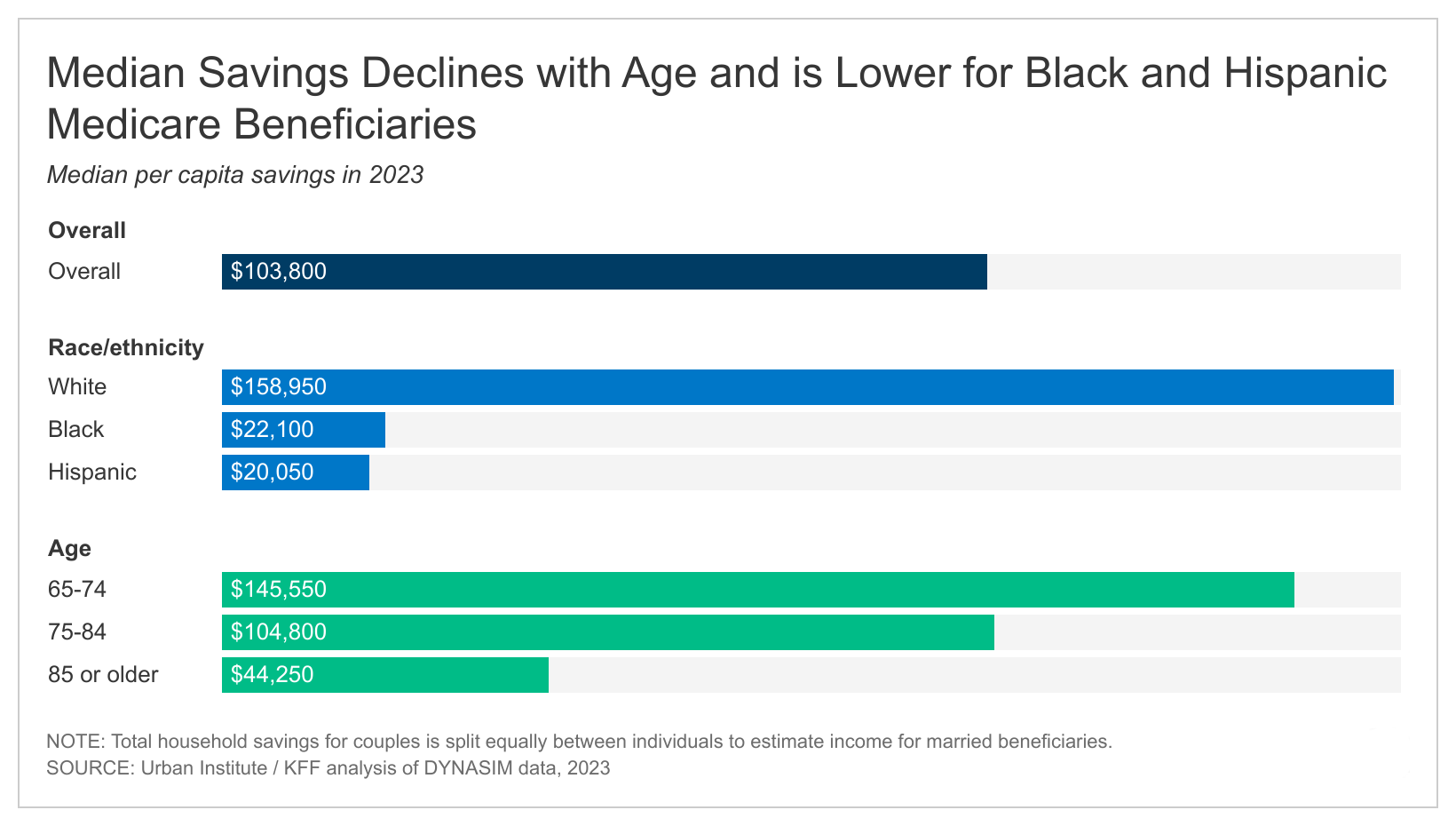

- One in four Medicare beneficiaries had savings below $16,950 per person in 2023, while half had savings below $103,800 per person. As with income, median savings declined with age among those ages 65 and older, were lower for women than men, and were substantially lower for Black ($22,100) and Hispanic ($20,050) than White ($158,950) beneficiaries.

- One in four Medicare beneficiaries had no home equity at all in 2023, while half of all Medicare beneficiaries had home equity below $124,450 per person.

- More than one in five Black and Hispanic beneficiaries had no savings or were in debt, compared to fewer than one in ten White beneficiaries. Nearly half of all Black and Hispanic beneficiaries had no home equity, compared to one in five White beneficiaries.

Income among Medicare Beneficiaries

In 2023, half of all Medicare beneficiaries (32.6 million) had incomes below $36,000 per person, while one quarter (16.3 million) lived on incomes below $21,000 per person. At the higher end of the income distribution, the top five percent of Medicare beneficiaries (3.3 million) had incomes above $138,500 per person, including the top one percent (0.7 million) whose incomes exceeded $259,150 per person (Figure 1).

Per person estimates of income varied by age, race and ethnicity, and gender, though nearly all beneficiaries across groups had at least some per capita income in 2023, in large part due to Social Security (Figure 2, Appendix Table 1).

Age: Among Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older, median per capita income declined with age, from $39,850 among those ages 65-74 to $28,650 among those ages 85 and older, a pattern which reflects, in part, a reduction in income from earnings among beneficiaries in older age groups and the lower likelihood of having income from earnings at older ages (for example, 46% of beneficiaries ages 65-74 had income from earnings in 2023, compared to 19% of those ages 75-84).

In 2023, roughly one in ten Medicare beneficiaries (11%) was under the age of 65. Younger beneficiaries, who are eligible for Medicare due to having a long-term disability, had the lowest median per capita income of any age group ($23,900 vs. $37,800 among seniors) and one in four lived on incomes below $15,000 per person (vs. $22,050 among seniors) (Figure 2).

Race/Ethnicity: Median per capita income was higher among White Medicare beneficiaries ($40,750) than among Black ($27,250) or Hispanic ($19,800) beneficiaries, reflecting wider racial and ethnic disparities in job opportunities and earnings during their working years, lower access to pension and other retirement benefits, and fewer years of education (Figure 2). Beneficiaries of color are also more likely than White beneficiaries to be under the age of 65 with long-term disabilities, to report being in fair or poor health, and to have one or more limitations in activities of daily living, impacting both their earnings during their working years and their ability to remain in the workforce as they age.

At the lower end of the income distribution, one quarter of Black beneficiaries lived on incomes less than $16,150 per person, and one quarter of Hispanic beneficiaries lived on incomes less than $11,850 per person, compared to $24,400 per person among White beneficiaries, which placed these Black and Hispanic beneficiaries near or below the federal poverty threshold of $14,580 for a single person in 2023 (Figure 2).

Sex: Median per capita income was lower among women than men ($33,750 vs. $38,950, Figure 2). On average, women have lower wages than men during their working years, even when working in similar roles, and often take on a larger share of unpaid family caregiving, resulting in lower lifetime earnings and lower Social Security benefits once they retire. These gender differences persisted across age groups among those age 65 or older, and across different racial and ethnic groups (Appendix Table 2).

Marital Status: Married beneficiaries had higher median per capita income ($42,000) than beneficiaries who were widowed ($32,950), divorced ($32,900), or single ($21,600) (Appendix Table 1). Spouses (or ex-spouses for marriages longer than ten years) can opt to receive half of their spouse’s Social Security benefit in lieu of the benefit based on their own earnings, which may offer greater flexibility to beneficiaries who are or have been married.

Education: Median per capita income rose with educational attainment and was more than three times higher among beneficiaries with a college degree ($62,150) than among beneficiaries with less than a high school education ($17,750, Appendix Table 1). One in three White beneficiaries held a college degree or higher in 2018 (32%) compared to 12% and 13% of Black and Hispanic beneficiaries, respectively, suggesting a relationship between racial and ethnic disparities in per capita income and years of education.

Savings among Medicare Beneficiaries

Half of all Medicare beneficiaries had savings below $103,800 per person in 2023, while one quarter had savings below $16,950 per person. One in ten (10%) had no savings or were in debt. Among the wealthiest Medicare beneficiaries, the top five percent had savings exceeding $1.6 million per person, including the top one percent whose savings exceeded $4.3 million per person (Figure 3).

Per person estimates of savings, as well as the share of beneficiaries without savings or with debt, varied by age, race and ethnicity, and gender (Figure 4, Appendix Table 1).

Age: As with income, median per capita savings declined with age among Medicare beneficiaries ages 65 and older, from $145,550 among those ages 65-74 to $44,250 among those ages 85 and older. By way of comparison, the median annual cost of care nationwide in 2021 was $108,405 for a private room in a nursing home, and $54,000 for an assisted living facility. Median per capita savings were lowest among beneficiaries with disabilities under the age of 65, half of whom had savings below $33,850 per person (vs. $119,350 among seniors) and one quarter of whom had savings below $4,650 per person (vs. $20,500 among seniors) (Figure 4). Roughly 15% of beneficiaries under age 65 (vs. 10% of seniors) had no savings or were in debt.

Race/Ethnicity: Median per capita savings among White beneficiaries ($158,950) were more than seven times higher than among Black beneficiaries ($22,100) and more than eight times higher than among Hispanic beneficiaries ($20,050) (Figure 4). At the bottom quartile of the savings distribution, average per capita savings among White beneficiaries ($34,450) were more than fifty times higher than among Black ($650) or Hispanic ($700) beneficiaries. More than one in five Black and Hispanic beneficiaries (22% and 21%, respectively) had no savings or were in debt, compared to just 7% of White beneficiaries. Racial and ethnic disparities in per capita savings are generally larger than disparities in income, and persist even among beneficiaries with similar levels of education, suggesting wider inequities in financial security and intergenerational wealth.

Sex: Median per capita savings were lower among women than men ($90,850 vs. $120,450) (Figure 4), and a larger share of women than men had no savings or were in debt (11% vs. 9%). Average life expectancy at age 65 is somewhat longer for women than men, and those with more modest wealth accumulation may be at greater risk of running out of retirement savings as they age. As with income, gender differences in savings persisted across beneficiaries in older age groups and by race and ethnicity (Appendix Table 2).

Marital Status: Married beneficiaries had median per capita savings ($169,200) that were more than twice as high as among beneficiaries who were widowed ($75,350) or divorced ($65,200) and more than six times higher than among beneficiaries who were single ($27,150, Appendix Table 1).

Education: Beneficiaries with a college degree had median per capita savings ($337,500) that were nearly six times higher than beneficiaries with only a high school degree ($60,800) and more than 34 times higher than beneficiaries with less than a high school education ($9,900, Appendix Table 1).

Home Equity among Medicare Beneficiaries

Half of all Medicare beneficiaries had less than $124,450 per person in home equity in 2023, while more than one quarter (26%) had no home equity at all (Figure 5). At the higher end of the distribution, the top five percent of Medicare beneficiaries had more than $846,900 per person in home equity, including the top one percent who had more than $1.4 million per person.

Per person estimates of home equity, as well as rates of homeownership, varied by age, race and ethnicity, and gender (Figure 6, Appendix Table 1).

Age: Median per capita home equity rose with age, from $132,550 among those ages 65-74 to $174,500 among those ages 85 and older, likely reflecting the larger share of homeowners who had reduced or paid off mortgage debt in older age groups. Unlike other financial assets, which may decrease as seniors leave the workforce and spend their accumulated savings, homes typically store and accumulate equity over time. Median per capita home equity was lowest among beneficiaries under the age of 65 ($14,050 vs. $142,200 among seniors), and one in two (48%) had no home equity at all (vs. 23% of seniors) (Figure 6).

Race/Ethnicity: As with income and savings, median per capita home equity was higher among White beneficiaries ($156,400) than among Black ($25,200) or Hispanic ($35,800) beneficiaries (Figure 6). This was due in part to differences in rates of homeownership, with close to half of Black (45%) and Hispanic (43%) Medicare beneficiaries having no home equity at all, compared to one in five (20%) White beneficiaries.

Sex: Median per capita home equity was somewhat higher among women than men ($131,650 vs. $116,050, Figure 6). While rates of homeownership were comparable (75% vs. 74%), differences in life expectancy mean that a larger share of women survive to older ages, allowing more time to accumulate home equity and, in the case of widowed beneficiaries, to own the full share of their homes.

Marital Status: The majority of married and widowed beneficiaries were homeowners, with median per capita home equity of $144,900 and $209,650, respectively. Just 13% of married beneficiaries and 20% of widowed beneficiaries had no home equity at all. By contrast, median per capita home equity among divorced beneficiaries was $53,500 and 41% were not homeowners. Single beneficiaries had the lowest rates of homeownership (63% had no home equity) with median per capita home equity of $0 (Appendix Table 1).

Education: As with income and savings, homeownership and median per capita home equity both rose with educational attainment. Among beneficiaries with a college degree, median per capita home equity was $232,650 and 15% had no home equity. Among beneficiaries with less than a high school education, median per capita home equity was more than 15 times lower ($15,400) and nearly half (47%) were not homeowners (Appendix Table 1).

Discussion

While a relatively small share of Medicare beneficiaries enjoy substantial wealth and financial security, most live on limited means, with significant disparities by age, sex, and race and ethnicity. Relatively low income and savings may present a particular challenge to Medicare beneficiaries under the age of 65, who are over three times more likely than older beneficiaries to report a problem paying a medical bill in the past 12 months, and nearly twice as likely to report delaying or forgoing a health care service, such as doctor visits or prescription drugs, due to their cost.

Living on a modest income and with limited savings may also prove challenging for Medicare beneficiaries in older age groups, particularly older women, who may be more likely to need expensive long-term services and supports for an extended period of time, such as home health aides or nursing home care, which Medicare generally does not cover.

Some Medicare beneficiaries may be eligible for additional support from Medicaid, including those with very low incomes and limited savings, and others who spend down their assets to pay for their medical or long-term care costs. Medicaid offers coverage for nursing home care and other long-term care services and supports that are not generally covered by Medicare. However, for lower and middle income beneficiaries who do not qualify for Medicaid, the high cost of unanticipated medical and long-term services and supports may simply be unaffordable.

Black and Hispanic Medicare beneficiaries have substantially lower incomes, savings and home equity than White beneficiaries, putting them at great financial risk in their retirement years, with fewer resources to cover unanticipated expenses. Beneficiaries of color are more likely than White beneficiaries to report difficulty accessing needed health care services. Cost-related barriers to care are especially common among Black beneficiaries, who are more than twice as likely as White beneficiaries to report a problem paying medical bills and more than three times as likely to report having an unpaid medical bill referred to a collection agency. Having less income to afford Medicare’s cost-sharing requirements or Medigap premiums contributes to a larger share of Black and Hispanic beneficiaries enrolling in Medicare Advantage plans. In doing so, they may face the tradeoff of access to supplemental benefits and lower cost sharing but more limited access to providers.

Policymakers have put forward a number of strategies to reduce the burden of health care spending for Medicare households. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 includes several provisions aimed at lowering prescription drug costs for people with Medicare, such as a cap on out-of-pocket spending under the Medicare Part D prescription drug benefit, a limit on insulin cost sharing under Medicare Part B and Part D, and expanded eligibility for the Part D Low-Income Subsidy (LIS), which assists with Medicare Part D drug plan premiums and cost-sharing. These provisions may allow Medicare beneficiaries to spend less on high-cost medications and reserve more of their income and savings for other health care needs, as well as food, housing and transportation, and other essential expenses. But high cost-sharing requirements and gaps in coverage, notably long-term services and supports and dental care, remain a pressing concern for the large swath of the Medicare population living on modest incomes and savings.

Alex Cottrill, Juliette Cubanski, and Tricia Neuman are with KFF. Karen Smith is with the Urban Institute.